HOW I FOUND LIVINGSTONE

HENRY MORTON STANLEY

SAMPSON, LOW, MARSTON, LOW & SEARLE, London, 1872

(Second Edition)

Dr. Reginald Larkin (1878-1958) was a Metropolitan Police Surgeon for over 30 years, from the Edwardian era until at least the mid 1930’s. He lived at 44 Trinity Square, Southwark all his life. His father, Dr Frederick Larkin had also lived there, and he too was a Surgeon. Frederick Larkin (1847-1927) had given crucial evidence in one of the most notorious Victorian murder trials, that of Henry Wainwright in 1875. The case became known as ‘The Whitechapel Tragedy', and Larkin performed the post-mortem examination of the victim, Harriet Lane. In November of the same year (1875) Larkin’s confident judgement and accurate evidence during the trial was largely responsible for Henry Wainwright's final conviction, winning handsome recognition from the Lord Chief Justice.

As a Police Surgeon with M Division of the Metropolitan Police, Reginald Larkin was involved in investigating numerous serious crimes, from the attempted murder of a policeman to serious assaults and gruesome domestic murders. An absolutely fascinating, and very readable record of his work has been preserved in the transcripts of trials held during the early 1900’s at the Old Bailey in London (www.oldbaileyonline.org). These accounts include the evidence Reginald Larkin gave in court, allowing us an invaluable insight into the forensic work of an Edwardian Police Surgeon. One particular case, Conrad Shelby's trial for murder, which took place in January 1912, includes Dr Larkin’s detailed testimony on the weapon used, the conclusions that could be reached from blood splatter patterns, and much other forensic information that would not seem out of place in a modern day courtroom. Another case, that of Charles Arthur from January 1911, concerned the attempted murder of a Policeman by a petty criminal armed with a revolver. While the officer, Constable Haytread, was giving chase, the assailant fired at him at least three times, missing each time, until he was tackled. In the ensuing struggle, Charles Arthur managed to hold the gun against Constable Haytread’s forehead and pulled the trigger. Incredibly, the gun failed to fire. The assailant was then overpowered and taken into custody. Dr Larkin’s main involvement in this case was to treat Haytread, who was clearly suffering from post-traumatic shock after this experience.

(I will include details of these trials and copies of other documents relating to Dr Larkin with the book. Included is a copy of the 1911 census for 44 Trinity Square which features the signature of Reginald Larkin and the address in his own handwriting. Coincidentally, Trinity Square has been used as a location in recent episodes of the BBC TV series ‘Sherlock'.)

Henry Morton Stanley (1841-1904), was one of the 19th century's most celebrated explorers. While engaged as one of the New York Herald's overseas correspondents in 1869, he was instructed by James Gordon Bennett Jr to find the celebrated Scottish missionary and explorer David Livingstone, who was presumed lost somewhere in Africa. Stanley travelled to Zanzibar in March 1871 and outfitted an expedition with the best of everything, requiring no fewer than 200 porters. This 700-mile expedition through the tropical forest soon became a nightmare. His thoroughbred stallion died within a few days after a bite from a Tsetse fly, many of his carriers deserted and the rest were decimated by tropical diseases. Stanley eventually found Livingstone on 10 November 1871, in Ujiji near Lake Tanganyika (in present-day Tanzania), and may have greeted him with the now famous, "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?" This famous phrase may be a fabrication, as Stanley later destroyed the pages of his diary relating to the encounter. Even Livingstone's account of the encounter fails to mention these words. However, a summary of Stanley's letters published by The New York Times on 2 July 1872, quotes the phrase.

The New York Herald account of the meeting, published on 2nd July 1872, also includes the phrase: "Preserving a calmness of exterior before the Arabs which was hard to simulate as he reached the group, Mr. Stanley said: 'Doctor Livingstone, I presume?' A smile lit up the features of the hale white man as he answered: 'Yes, that is my name' . . ."

Stanley proceeded to join Livingstone in further exploring the region, establishing that there was no connection between Lake Tanganyika and the River Nile. On his return, he wrote How I Found Livingstone; travels, adventures, and discoveries in Central Africa, the book that brought him fame and financial success.

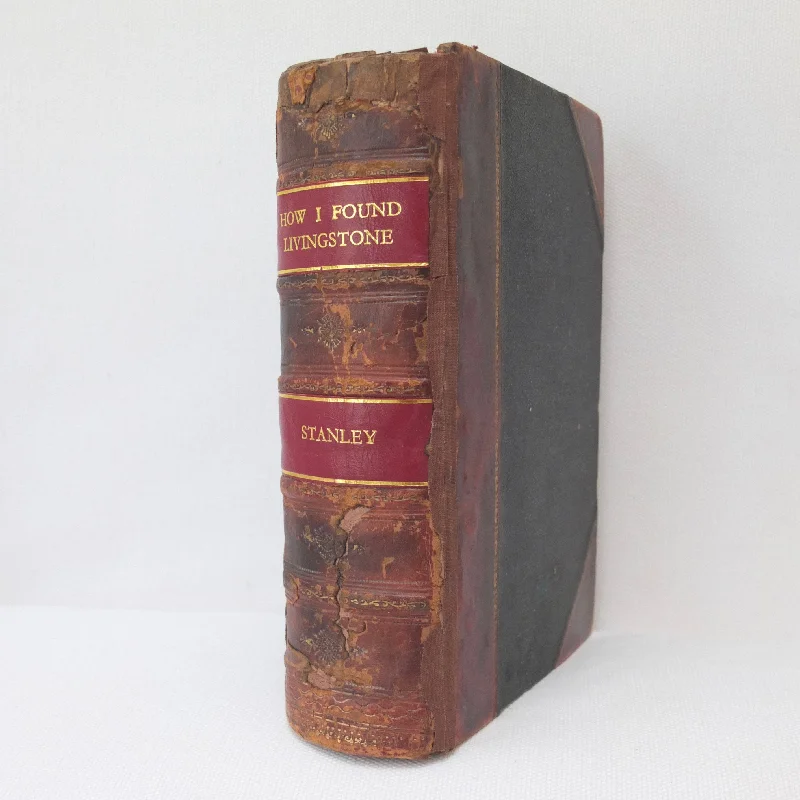

Condition:

In fair condition. The boards are in fair condition, with general signs of wear, marks, and wear to the edges. The leather spine is very worn, with some small pieces missing, and has been repaired in several places and at the edges. The spine title labels have been replaced. Despite the obvious wear, the hinges and binding are secure, the front hinge having been reinforced with archival tape. The text and illustrations are in good condition, with general signs of use and some marks. There should be six maps, but five of these are missing. The book is signed on the front endpaper by ‘R. Larkin M.D., 44 Trinity Sq, Southwark’.

Published: 1872

Second Edition (same year as 1st)

Quarter leather binding, green boards, leather & gilt spine labels

Illustrated with numerous full page plates and other engravings

Pages: 736

Dimensions: 150mm x 220mm